[I originally shared this post on Medium, but I've since moved here.]

If you're like me, you've probably seen the Dunning-Kruger curve once or twice in a meme or slide deck and quietly huffed out your nose, thinking:

“Ha! Look at all those overconfident dummies. I know I don't know anything. That must mean I'm smart.”

Then you went about your day, basking in the warm glow of your intellectual humility.

Fig. 1 — I am very smart. (image source)

But in a late-night Wikipedia rabbit hole, I stumbled upon the original paper, Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments(Kruger & Dunning, 1999).

And that's when the real horror set in.

It turns out that that familiar graph has been widely misinterpreted. The paper wasn't about intelligence at all. It revealed a sharper, more specific cognitive bias:

People with low ability in a given domain tend to significantly overestimate their competence in that same domain.

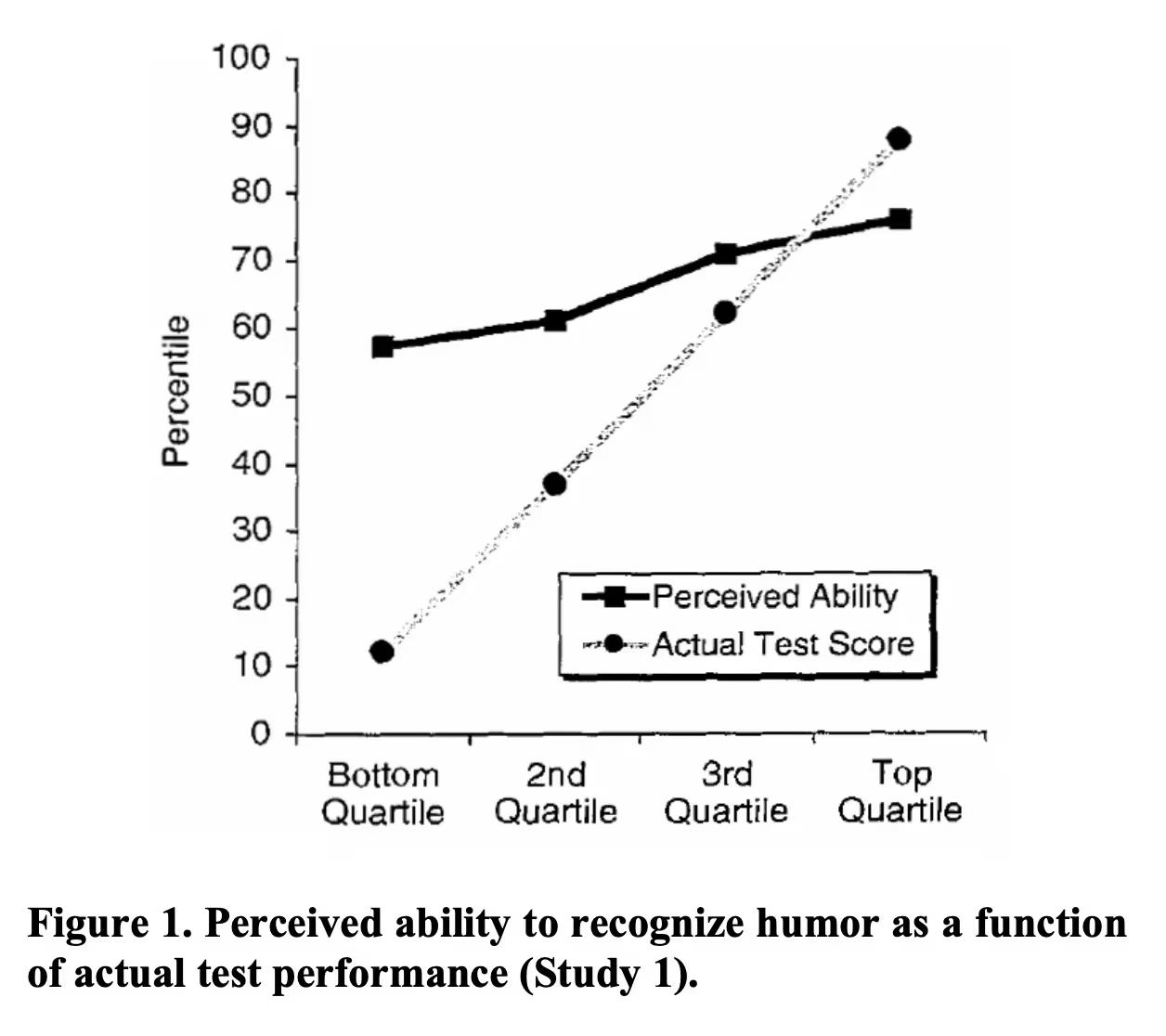

And the actual graphs? They looked more like this:

Real Fig. 1 — Wait a moment. (Kruger & Dunning, 1999)

Real Fig. 1 — Wait a moment. (Kruger & Dunning, 1999)

It hit me. In misunderstanding the Dunning-Kruger effect, I had become its poster child.

I had overestimated my understanding of a concept about overestimation. My fleeting glances at a few memes gave me just enough awareness to feel informed but not enough to avoid fundamentally misinterpreting the idea.

I was horrified. My fragile self-image shattered.

So naturally, this got me thinking about generative AI.

Problem

Gen AI is incredible in the truest sense of the word. ChatGPT's Deep Research has reduced the barrier to surface-level knowledge across nearly any domain from hours or days down to minutes. In less than an hour, tools like Lovable.dev, Bolt, and v0 can vibe-code you a functioning full-stack, multi-tenant SaaS app, complete with a database and authentication.

But this profound shift doesn't just mean that people are learning more quickly — it means that more people are stepping into unfamiliar domains armed with just enough information to feel fluent, just enough tooling to deliver something that works, and not quite enough context to think critically or question flawed assumptions.

This is exactly where the Dunning-Kruger effect kicks in.

I want to be emphatically clear: I'm not suggesting that the Dunning-Kruger curve is changing shape. I'm making no claims about percentiles, the delta between perceived and actual ability, or people getting dumber. However, the volume of people moving from zero to some competence is increasing, and with them, so is the volume of confidently wrong ideas.

That includes all of us.

At high-growth companies, we're often explicitly asked to move boldly and with a bias for action, a vital directive that inherently carries risk. When the cost of slowing down feels higher than the cost of being wrong, it's easy to charge ahead without realizing we're building on shaky foundations.

I've been involved in projects that should have taken days stretch into weeks because two people thought they were aligned, only to discover that one person meant W, asked for X, the other heard Y, and we ended up with Z.

These failures didn't come from bad intentions. They came from confidence built on flawed assumptions, under pressure, without pause.

And while the ideal is to fail fast, we often fail slowly, burning time, money, and trust in the process. We can move fast, but when we fall, we hit the pavement hard, and there's only so much skin we can lose.

This isn't a call to move cautiously. Taking risks is critical to long-term success. But smart speed means pausing long enough to check our footing before we start running.

We will all continue to make mistakes. The goal isn't to eliminate them but to avoid the preventable ones and make the smart ones instead. Smart mistakes are the kind that come from well-reasoned decisions, clear tradeoffs, and thoughtful bets that teach us something and move us forward.

Courses of Action

Think of the Tokyo and NYC subway systems: conductors point at signals and signs not to slow things down but to force attention. The purpose is to interrupt automatic behavior just long enough to prevent high-impact mistakes.

A train conductor pointing and calling. (image source)

A train conductor pointing and calling. (image source)

We need similar lightweight rituals that force us to pause and think clearly. The more confident we feel, the more important it is to stop and ask, “Do I really know what I think I know?”

I don't have all the answers, but here are three tools I've been experimenting with to push toward first-principles thinking:

The Five Whys

Low complexity. Easy to remember. Instinctual toddler logic. I fall back on it in conversations or when I'm caught off guard.

Classically, the Five Whys is a method of root cause analysis that asks “Why?” repeatedly (usually five times) to move past surface-level reasoning and uncover what's really going on.

That said, using the word “Why?” can quickly feel confrontational and accusatory, so rephrasing into “How?” or “What?” questions can keep conversations collaborative and focused on truth-finding.

If you land on a statement of falsifiable fact, you've likely hit a first principle. If you land on something like, “because we've always done it this way,” “because I said so,” or “it just is,” then you've probably uncovered an assumption rooted in habit that's worth breaking down.

These conversations don't need to be formal or forced. They're just about slowing down enough to notice when we've stopped asking questions.

Example: Why are we always eating dinner so late?

Statement: “We need to start cooking earlier.”

What makes us think cooking is the issue?

We usually don't eat until 9 p.m., and dinner's never ready on time.

What's keeping us from starting earlier?

We're usually still wrapping up work or errands.

What's causing work and errands to run late?

We don't really have a fixed stopping point. We just keep going until it feels done.

How are we deciding when to stop?

We're not. We're reacting to whatever comes up.

What could help us protect time for cooking?

Setting a hard cutoff time and planning for errands earlier in the day.

Possible first principle uncovered: The problem isn't when cooking starts, it's that nothing is protecting time.

(Note: You can probably go even deeper and start questioning everything — your life, job, career, family — but practically, you have to stop somewhere.)

Socratic Process

Higher complexity. Slower to use. More comprehensive. I rely on this when reviewing documentss, thinking through tough decisions, or when something just feels off but I can't explain why.

It's broader and more structured than the Five Whys. I've pulled a version from The Great Mental Models by Shane Parrish that breaks the process into six steps:

Step 1: Clarify your thinking and explain the origins of your ideas.

Why do I think this? What exactly do I think?

Step 2: Challenge your assumptions.

How do I know this is true? What if I thought the opposite?

Step 3: Look for evidence.

How can I back this up? What are the sources?

Step 4: Consider alternative perspectives.

What might others think? Why would they believe that? How do I know I'm correct?

Step 5: Examine consequences and implications.

What if I'm wrong? What are the consequences if I am wrong?

Step 6: Question the original question

Why did I think that? Was I correct? What conclusions can I draw from the reasoning process?

![Meme with text: Random Athenian: claims to know something. Socrates: [image of Count Dooku (Star Wars: Episode III — Revenge of the Sith (2005))stating, ‘I've been looking forward to this.']](/overconfident/count-socrates.avif) Thank you for making it this far. (image source)

Thank you for making it this far. (image source)

The Liberating Honesty of "I don't know, yet."

People will ask you for time estimates. This is normal, you cannot escape it, and those estimates will impact planning across multiple workstreams.

If you don't know, that's okay. Acknowledge it with an honest answer that's still useful:

“I don't have a good answer right now. If I had to guess, it would be on the order of [minutes/days/weeks/months/years/geological eras/other time units], but let me get back to you in two hours after I've thought it through.”

The key is to actually use that time to think through the problem, question assumptions, look at the impacted systems, and come back with an estimate based on something real and not a gut feeling that's off by orders of magnitude.

Bonus win: by thinking through the chokepoints, you'll probably already know the answer to the inevitable follow-up:

“How can we accelerate this?”

This matters. A guess of “a few days” that turns into “a few weeks” and then into “a few months” doesn't just miss an arbitrary deadline. It creates chaos and miscommunications across teams, stakeholders, and clients.

It's almost always much better to pause for two hours at the start than to miss a project than to miss by several weeks at the end.

Closing

We don't need to slow down, but we can stop sprinting with our eyes closed.

This isn't about being cautious. It's about using a few tools to be just thoughtful enough to avoid preventable mistakes and make smart mistakes instead.

Ask questions. Be honest about what you don't know. Remember that being confident is not the same as being right.

References

Parrish, S., & Beaubien, R. (2024). The Great Mental Models, Volume 1: General Thinking Concepts. Penguin.

Kruger J, Dunning D. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999 Dec;77(6):1121–34. doi: 10.1037//0022–3514.77.6.1121. PMID: 10626367.